Growing up in the desert of Australia’s Northern Territory, but planting my roots in the forests of England, landscape is what feeds me. I’ve enjoyed roles as web editor for Digital Earth Australia, deputy editor on Australian Geographic Outdoor magazine, road warrior on the Ocean Film Festival World Tour, and marketeer for the Banff Mountain Film and Book Festival. I’ve studied Urban Forestry at the University of Melbourne, Sustainable Leadership at the University of Cumbria, graduate research in Landscape Architecture and executive training in Environmental Communication for Behaviour Change.

IMAGERY FOR IMPACT: Songlines soar for science and country

“Growing up, learning about the environment was the same as learning about myself,” says Reuben House, a 26-year-old Ngambri-Wiradjuri man and firefighter with ACT Fire and Rescue.

“Growing up, learning about the environment was the same as learning about myself,” says Reuben House, a 26-year-old Ngambri-Wiradjuri man and firefighter with ACT Fire and Rescue.

“Your Country — and how you care for it — is your identity. When I’m painting, I’m trying to pass on my knowledge about the Ngambri (or ‘Kamberri’) Country around Canberra, its songlines, explaining the beliefs and laws of my tribe to the rest of Australia.”

The artist has created two pieces for the Geoscience Australia, depicting an Eagle and a Crow — two significant totems for the Ngambri people. The birds are shown soaring over the mountains and waterways of the ACT.

“It was just a creative moment,” says Dr Mark Broomhall, Chief Remote Pilot with the Digital Earth Australia program, of the idea that sparked Reuben’s commission to paint his Eagle and Crow. “This year we welcomed a new drone into our fleet of remotely piloted aircraft — a Noa-H6. This is the apex predator of drones.

“We thought we’d like to give the new drone a name and we wanted to find a local name for the wedge-tailed eagle. Thanks to Reuben and the Ngambri community, the Noa is now named Mallian, and the others are named Budyan, meaning ‘bird’ in general.”

The drones fly optical sensory equipment over otherwise inaccessible landscapes for the DEA Analysis-Ready Data team. The data they capture is used to validate information received from satellites in orbit against what can be observed on the ground — ensuring the accuracy of digital maps of land cover, coastal erosion, deforestation, waterbodies, floods and bushfires.

ORD VALLEY MUSTER: Shindig of the year in the East Kimberley

Moon morning, Kununurra is humming with an electricity that smells of a wedding, or Christmas Day. The markets are on, selling pickled boab, bright pink felt nappies, and bumper-stickers supporting the Kimberley Toad Busters.

Moon morning, Kununurra is humming with an electricity that smells of a wedding, or Christmas Day. The markets are on, selling pickled boab, bright pink felt nappies, and bumper-stickers supporting the Kimberley Toad Busters.

Triathletes run through town and 32º heat. In the Ivanhoe café, gaggles of women laugh over mango smoothies and melon salads in a flowered garden. The abundance of succulent fruit and veggies feels incongruous in the middle of the red East Kimberley, but with a freshwater lake system larger than Sydney Harbour at its doorstep, Kununurra plants whatever it fancies, and shower heads are luxuriously large.

By mid-afternoon, town is in torpor. Shops are closed, the markets have vanished, and the only activity is a gang of kids diving for a coin in the town pool. A warm silence settles on the Ord River, and the Celebrity Tree Park, with its Boab planted by Baz, and Cathormion by Rolf, is empty but for a greying black dog sitting under a Freshwater Mangrove planted by Andrew Daddo.

Hairspray, perfume, and pink Kimberley diamonds are applied liberally across town, soon emerging from air-conditioning into the evening. On minibuses people sit on each other’s laps and visitors recognise one another from the year before.

On the Moon Stage by the banks of the Ord, the town choir has already performed to children and proud grandparents, the Mirima Dancers have welcomed the event and Chris Matthews, a ranger at the nearby El Questro Wilderness Park, soon to release his next album entitled I Haven’t Heard Of You Either, entertains the swelling crowd.

Little tackers – some in their prettiest laced dresses, others barefoot and gummy-nosed – clutch glow-sticks and run in circles until they are dizzy and fall in the dust. As the full moon rises and the Ord licks the cooling riverbank, there is the rustle of plastic wine glasses, Cheezels packets and stubbies being fished from melting ice.

AUSTRALIANS WARMING to green giving

“Most Australians really do care about the natural environment,” says Amanda Martin, Executive Officer of the Australian Environmental Grantmakers Network (AEGN).

“Most Australians really do care about the natural environment,” says Amanda Martin, Executive Officer of the Australian Environmental Grantmakers Network (AEGN).

“They have a deep connection with the beach, the bush, or with the Great Barrier Reef. Australians identify as being people who love their environment, but when it comes to environmental philanthropy, they can feel lost.”

Established in 2009, the AEGN is a member-based body that exists to navigate funders through the journey of financing environmental causes and projects. At its inception, it gathered 25 members. Five years later, its numbers have more than tripled.

“We act as a kind of philanthropic concierge,” Martin says. “Introducing people to one another, finding out what funders’ wants and needs are, and connecting them with the right organisations. We provide mentors and translate the environmental sector for philanthropists.”

Big, old forest philanthropy now provides the canopy for the group’s growth: the likes of Myer, Ian Potter, R E Ross, and the Reichsteins.

“We’re the first to admit that when we started out, we were a group of people drawn together by a lack of knowledge – by a want for education,” Martin says. “Now many of our members have experience in what does and doesn’t work – they are sharing that with new people, and trust the membership to make the most of their learning.”

AN EXPLOSIVE REIMAGINING: Melbourne RBG

With more than 50,000 thirsty plants to tend, the staff at Melbourne’s Royal Botanic Gardens have had water on the brain for a long time.

With more than 50,000 thirsty plants to tend, the staff at Melbourne’s Royal Botanic Gardens have had water on the brain for a long time.

Before climate change, sustainability, and conservation were budding concepts, 1870s Director of the Gardens, William Guilfoyle, was cultivating smart design concepts to maximise the park’s water retention.

In 1876, he developed a crater-like water reservoir at the highest part of the Gardens to gravity-feed lower areas and make the most of Melbourne’s rainfall. The reservoir was called Guilfoyle’s Volcano and featured flowing lava-like lawns and flowerbeds that dribbled downhill to create a whimsical “folly”.

For more than 60 years, Guilfoyle’s Volcano lay derelict – a forgotten feature of the Gardens – until 2010 when it was revived as Stage 1 of The Royal Botanic Gardens’ 3 Stage Water Strategy Project.

Since 1994 water consumption in the Gardens has been reduced by more than 60 per cent, and at the completion of its Strategy Project, the management team hopes to “turn off the tap” – for the site to become completely drought-proofed, never again reliant on Melbourne mains water.

Philanthropic support for the 3 Stage Water Strategy Project has included significant funding from The Myer Foundation and Sidney Myer Fund 2009 Commemorative Grants Program, Melbourne Water, South East Water Limited, Royal Botanic Gardens Foundation, Friends of the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne Inc, The Calvert-Jones Foundation, Ken and Jill Harrison, and Peter Jopling QC.

RAFTING REMOTE NEW ZEALAND: Let the wine breathe

‘Air’ is a theme in Queenstown. Some well-meaning copywriter has developed an entire marketing package around it, and from the moment I step into the airport, I am in labour. “Breathe!” it commands, “Close your eyes and take a deep breath!” I look at the face of the bungee-jumping backpacker whose eyes are very much closed as he is inhaled by gravity towards a huge spinning rock, and am sceptical.

‘Air’ is a theme in Queenstown. Some well-meaning copywriter has developed an entire marketing package around it, and from the moment I step into the airport, I am in labour. “Breathe!” it commands, “Close your eyes and take a deep breath!” I look at the face of the bungee-jumping backpacker whose eyes are very much closed as he is inhaled by gravity towards a huge spinning rock, and am sceptical.

Two days later I am in the air again. The Landsborough River is wide and wiggly in most places, and I delight as my body ascends over it in our chopper. I want to swim upwards with my arms, flail them about in a celebration of my sudden weightlessness, (weightlessness over wiggliness!) but instead keep them where the pilot instructs. Taking off feels like coming up from under a wave …

THINGS TO KNOW BEFORE YOU GO – HYDRATION

No prior rafting or paddling knowledge is required to enjoy a Landsborough experience, but a basic understanding of South Island wines would go a long way. Rolling juicy vineyards bathing in yellow Otago sunlight are so common in the Queenstown/Wanaka area that they look like native grasses. Essential facts to keep you afloat when the corks are screwed include:

1. Slapped on the 45th parallel, the Central Otago wine region is the most southerly wine producing region in the world. At 200 to 400 metres above sea level, it is also the highest in New Zealand. These unusual geographical features complement a unique climate to make the region prime for the growing of the dark Pinot grape.

2. Queenstownies are so proud of their Pinot that they hold an annual January festival to celebrate it (www.pinotcelebration.co.nz). They are equally, if not more proud, to tell you that Jurassic Park’s Sam Neill owns a vineyard in the area. Sam’s label is called Two Paddocks, and their 2006 Pinot is “youthful, but bold and assertive”.

3. Don’t waste time flirting with the many other quality New Zealand wines that accompany a Landsborough trip: sharpen your elbows and make straight for the Pinot, or it will be gone before you have finished your first prawn.

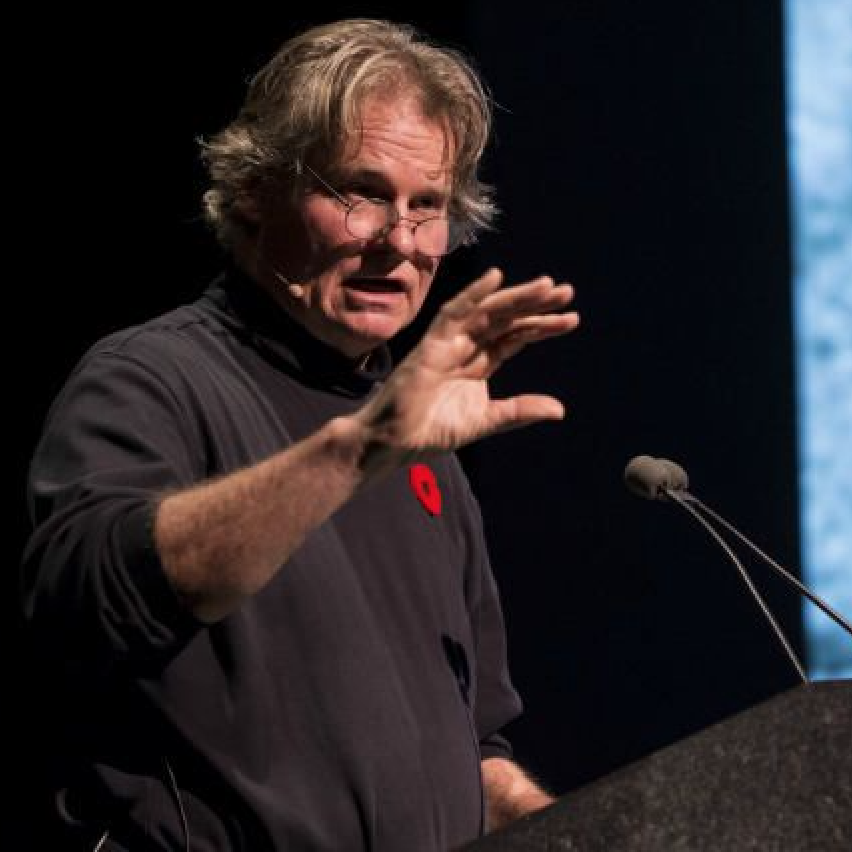

AT THE TIPPING POINT: Wade Davis

Wade Davis, a man described as “part Indiana Jones, part James Bond” is an author, photographer, Explorer-In-Residence at the National Geographic Society, and one of the founding fellows of the International League of Conservation Photographers – the group responsible for bringing exhibitions ‘Sacred Headwaters – Sacred Journey’ and ‘Great Bear Rainforest’ to this year’s Banff Mountain Film Festival. The ILCP is an organization of 106 of the world’s top professional photographers, including Davis, who donate their time to shoot regions with ‘tipping point’ environmental or cultural conservation issues. Images then travel in exhibitions, publications, and events to promote awareness and support. To the ILCP, the areas featured in The Banff Centre exhibits – BC’s Stikine, Skeena, and Nass rivers, and its Great Bear Rainforest – all fall under this mandate. At yesterday’s exhibition opening, Davis took the lectern:

Wade Davis, a man described as “part Indiana Jones, part James Bond” is an author, photographer, Explorer-In-Residence at the National Geographic Society, and one of the founding fellows of the International League of Conservation Photographers – the group responsible for bringing exhibitions ‘Sacred Headwaters – Sacred Journey’ and ‘Great Bear Rainforest’ to this year’s Banff Mountain Film Festival. The ILCP is an organization of 106 of the world’s top professional photographers, including Davis, who donate their time to shoot regions with ‘tipping point’ environmental or cultural conservation issues. Images then travel in exhibitions, publications, and events to promote awareness and support. To the ILCP, the areas featured in The Banff Centre exhibits – BC’s Stikine, Skeena, and Nass rivers, and its Great Bear Rainforest – all fall under this mandate. At yesterday’s exhibition opening, Davis took the lectern:

“Canada is not about nationalism,” he said. “It’s about landscape; the beauty of the country that nurses our children, that gives us life, and that was the inspiration for our grandparents … Wherever you go, Canadian mining companies are doing terrible things. It’s become shameful for those of us who are Canadians.

“Here we were, this extraordinary country with this amazing reputation, a country whereby the ‘north’ hovered in the imagination and define the essence of our national soul, and now we have become a laughing stock to the world. I was at Copenhagen, and our country was utterly mute because of the tar sands. Everything comes back to the tar sands … Canadians really have to make a choice: what kind of country do we want to be? We have the opportunity to be a country that is an exemplar to the world, not an embarrassment. If we can’t stop the tar sands, at least we can say that we will not allow their cancer to infuse everything else that we do in our landscape. This is what these photographs are about.”

MONTAGUE ISLAND: Where the winged ones go

On a recent National Parks and Conservation Volunteers excursion to Montague Island, 9km of the south coast of NSW, I spent three days picking weeds and writing the very small, salty space into my history. At the end of the volunteer program, I asked Louise, our ranger and guide, what it was that she thought was most powerful about the island.

On a recent National Parks and Conservation Volunteers excursion to Montague Island, 9km of the south coast of NSW, I spent three days picking weeds and writing the very small, salty space into my history. At the end of the volunteer program, I asked Louise, our ranger and guide, what it was that she thought was most powerful about the island.

I expected her to say something about the ongoing relationship brokering of Australian with their landscapes; of the importance of reintroducing native vegetation to a site of significance for so many breeding birds; something about making a connection with the lives if the keepers, and the their families, who endured sickness and solitude to serve the island’s lighthouse for 100 years.

She paused, looked from the light-station kitchen out to where others of our group were watching dolphin and Humpback whale pods feed in the dull morning sea.

“The quiet,” she said. “The chance to be still.”

For a place with a soundtrack Hitchcock would envy, it was an ironic reflection.

PICKING UP PLASTIC: Take 3 on the beach

Like many coasties, I’ve been removing rubbish from my local beach for years. Plastic drink bottles, chip packets, straws, more straws, the wreckage of Styrofoam cups, ironic sushi soya-sauce fish bottles. On my own, collecting rubbish feels cathartic. The ‘Grand Challenges’ facing our oceans feel slightly less grand. The not-so-Great Pacific Garbage Patch is denied my four plastic straws; one seagull is saved the shame of limping through a shortened life wearing unfashionable fishing line.

Like many coasties, I’ve been removing rubbish from my local beach for years. Plastic drink bottles, chip packets, straws, more straws, the wreckage of Styrofoam cups, ironic sushi soya-sauce fish bottles. On my own, collecting rubbish feels cathartic. The ‘Grand Challenges’ facing our oceans feel slightly less grand. The not-so-Great Pacific Garbage Patch is denied my four plastic straws; one seagull is saved the shame of limping through a shortened life wearing unfashionable fishing line.

In a social group, however, collecting rubbish feels truly righteous.

Pausing mid-beach-walk to pocket plastic can disrupt a conversation in the best of ways. The statement that is made by bobbing to collect other people’s trash on the way to the showers is unspoken but unmistakeable: Now see here.

For many years, I’ve felt that my upright (bent over) marine citizenship was contribution enough. Not so for marine ecologist Roberta Dixon-Valk, community educator Mandy Marechal, and environmental management professional Tim Silverwood. Five years ago, the three NSW Central Coast residents took their personal plastic picking to a new level, and united to found Take 3.

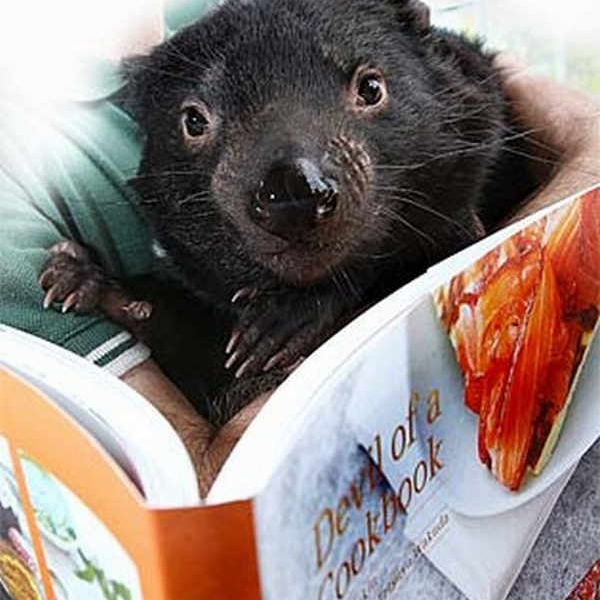

DEVILISHLY DELICIOUS IMPACT: Cooking for conservation

In 2008, the Tasmanian Devil was declared an endangered species. Since the late 1990s, its numbers have been decimated by Devil Facial Tumour Disease (DFTD) – a contagious cancer that mainly affects the mouth and neck, is transmitted between devils through biting, and which kills the animals through an agonising starvation.

In 2008, the Tasmanian Devil was declared an endangered species. Since the late 1990s, its numbers have been decimated by Devil Facial Tumour Disease (DFTD) – a contagious cancer that mainly affects the mouth and neck, is transmitted between devils through biting, and which kills the animals through an agonising starvation.

According to the Parks and Wildlife Service of Tasmania, more than 90 per cent of the adult Devil population living in high-density areas of the state has been eradicated by DFTD. An estimated 40-50 per cent of animals living in medium-low density areas have also been affected.

For British-born animal behaviourist Bruce Englefield and wife Maureen, one-time owners and operators of a wildlife park on Tasmania’s east coast, the Devil problem was too virulent to ignore.

In 2007, they established the nonprofit Devil Island Project Group (DIP), and on the same day that the Devil was listed as endangered in 2008, the first ‘Devil Island’ was officially opened and stocked with disease free Devils on 11 hectares of land the couple had donated to the Tasmanian government.

Also in 2007, the then 64-year-olds recruited eight Tasmanians to train with them to run in the 2008 London Marathon as a fundraising event for Devil defence. Maureen described the run as “worse than childbirth”. Together, the ‘Devil Islanders’ raised $170,000 to fully fund the building of this first Devil Island.

So began a seven-year battle to help save the Tasmanian Devil, and a mission to build and manage ‘Devil Islands’ throughout Tasmania.