“I’M AFRAID IT’S TOO LATE FOR YOU,” author Robert Kroetsch once told me. “You’re an artist. You can’t go back. It’s like getting pregnant: Oops! Art is gestating.”

I still disagree with the old man about myself, but after two years and four roles in communications and festival coordination at Canada’s leading creativity-incubator, The Banff Centre, I understand what he meant about art. I’ve written about jazz, dance, spoken word, theatre, literature, film, even puppetry. Through Generosity, an Australian philanthropy magazine I helped to launch, I’ve also met many of that nation’s leading arts organisations and funders. In the end, art is just a bodily function. Kroetsch knew that.

GENE SHERMAN: “Tikkun olam – Mend the world”

Within minutes of meeting Dr Gene Sherman – philanthropist, academic, chairman and executive director of the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation (SCAF) – it becomes clear why she wears so much black.

Within minutes of meeting Dr Gene Sherman – philanthropist, academic, chairman and executive director of the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation (SCAF) – it becomes clear why she wears so much black.

Sherman herself would explain her monochromatic aesthetic as idiosyncratic, influenced by pioneers of Japanese fashion, an intellectual and emotional expression of form. But listening to her South African lilt over tea in the sunlit SCAF garden, I think her blackness is about warmth. The retaining of it, the effusing of it, the spilling of it onto guests, gallery staff, family, the workmen who have arrived to install a new artwork in the garden. Like heat off bitumen.

A Member of the Order of Australia, grandmother of six, a ‘Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres’ (one of France’s highest honours, also bestowed on T.S Eliot and Seamus Heaney), and matriarch of one of Australia’s most esteemed and accomplished Jewish families, Sherman’s seemingly blessed life has not been without its darkness.

A child of Apartheid South Africa, her blossoming years were coloured with the unpredictable fortunes of her brilliant but ill-fated financier father, the suicide of her mother Micky, the loss of her brother Peter, and the later stillbirth of her first child with husband Brian, who she had met at a tennis match and wed 12 weeks later.

When Gene and Brian arrived in Sydney in 1976, carrying two young children and a total of $5200, it was to build anew. “We felt empowered to make a wonderful life. We just wanted to get on with it.”

A DEEP DIVE into bio-artscapes

Every Wednesday afternoon at Melbourne’s Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, visitors are chaperoned through the Institute’s impressive Parkville campus for a public tour.

Every Wednesday afternoon at Melbourne’s Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, visitors are chaperoned through the Institute’s impressive Parkville campus for a public tour.

Groups learn WEHI history as they move through the Discovery Timeline Tunnel, and listen as enthusiastic junior scientists give lab demonstrations of their current work, but it’s Drew Berry’s on-screen biomedical animations—also enjoyed by hundreds of thousands of online viewers—that really hit visitors between the eyes. Berry’s animated films and audiovisual installations are Willy Wonkaesque rides through the molecular landscapes of cells and diseases.

True to both scale and speed, if his Emmy and British Academy of Film and Television Association award-winning creations were not widely acclaimed for their data-based scientific accuracy (informed by an average of 100 research papers per frame), they’d be the stuff of dreams.

A trained cell biologist and microscopist, Berry had a childhood fascination with horror films, computer graphics and the deep-sea adventures of Jacques Cousteau that outgunned his early career as a researcher. His role as head of WEHI TV has incubated an artist that The New York Times describes as the “Steven Spielberg of molecular animation.”

COOL KIDS ON CAMPUS: Indie Band Residency

Morning coffee queue at The Banff Centre’s Maclab Bistro, and the line-up consists of the usual suspects: a poet with a post-yoga glow, a sculptor in a postparty funk, and a conference suit with a pre-caffeine twitch. At the front of the line, two girls in knee-high boots, sequinned silver skirts, and massive, winged fur coats wait for their skim lattes. I sneak a glance at the taller one – her brown hair teased into an electrified madness, one glittering oversized eyelash peeling away from her face. The girls/women/amazons look as though they have fought the wilds for this coffee. Small pieces of bracken fall from their hair onto the floor.

Morning coffee queue at The Banff Centre’s Maclab Bistro, and the line-up consists of the usual suspects: a poet with a post-yoga glow, a sculptor in a postparty funk, and a conference suit with a pre-caffeine twitch. At the front of the line, two girls in knee-high boots, sequinned silver skirts, and massive, winged fur coats wait for their skim lattes. I sneak a glance at the taller one – her brown hair teased into an electrified madness, one glittering oversized eyelash peeling away from her face. The girls/women/amazons look as though they have fought the wilds for this coffee. Small pieces of bracken fall from their hair onto the floor.

“Music video,” one of the she-beasts says with a tired smile in response to my staring. “Indie Band,” she adds. It all becomes clear. The cool kids.

I am about to slink away with my herbal tea to my way uncool day job when the king of the cool kids shuffles in. With long, dishevelled hair, an old-man cardigan, and the kind of loafers Jesus would wear if he was a drummer/producer/audio-engineer wunderkind, “Hey”, Shawn Everett says to me, just like he says hey to Bob Dylan, or Eddie Vedder in his real life. “Hey Shawn”, I say back so that the musicvideoettes can hear. For a brief moment, I too, rock.

The Banff Indie Band Residency, a two-week program for indie rock groups is in its third session, and the energy it is putting out is far from acoustic. An intensive writing, recording, and performance program in which three up-and-coming groups are given access to the kinds of resources for which most musicians wait a lifetime, the program is one big amplified band camp. Three bands, Winnipeg’s Mise en Scene, Vancouver’s Abramson Singers, and Doldrums from Toronto/Montreal, have been chosen to board the Banff Indie Band train.

STABLE-ISING INFLUENCE: Reimagining the Melbourne Arts Precinct

$42.5 million will redevelop Melbourne’s historic Dodds Street police stables into a visual arts wing at the Victorian College of the Arts.

$42.5 million will redevelop Melbourne’s historic Dodds Street police stables into a visual arts wing at the Victorian College of the Arts.

Announced last week by the University of Melbourne and the Victorian Government, the redevelopment project will strengthen the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) and Melbourne Conservatorium of Music’s (MCM) position in the centre of Melbourne’s Arts Precinct.

The VCA win comes in on the heels of the recent release of a $900,000 study, ‘The Melbourne Arts Precinct Blueprint’ by the state government and is a significant milestone for Believe, the Campaign for the University of Melbourne. The four-year campaign was launched in May 2013 to help the University better tackle the next century’s “grand challenges”; understanding place and purpose, fostering health and wellbeing, and supporting sustainability and resilience.

Major gifts to the Campaign, including $5 million from the Ian Potter Foundation, $4 million from the Myer Foundation, and $1 million from Martyn and Louise Myer, played a key role in the getting the Dodds Street project out of the gates. Victorian Premier Denis Napthine said the redevelopment would transform the VCA and MCM campus in Southbank into an exciting destination for arts and cultural activity.

“The redevelopment project – the largest in the history of the VCA – will create public performance, event and exhibition spaces across the campus and surrounding streets, as well as a series of laneways, public thoroughfares and gardens,” Dr Napthine said.

Built in 1912, the Dodds Street stables were constructed “within fast galloping distance” of Government House.

SCHOLARSHIPS BY THE SEA

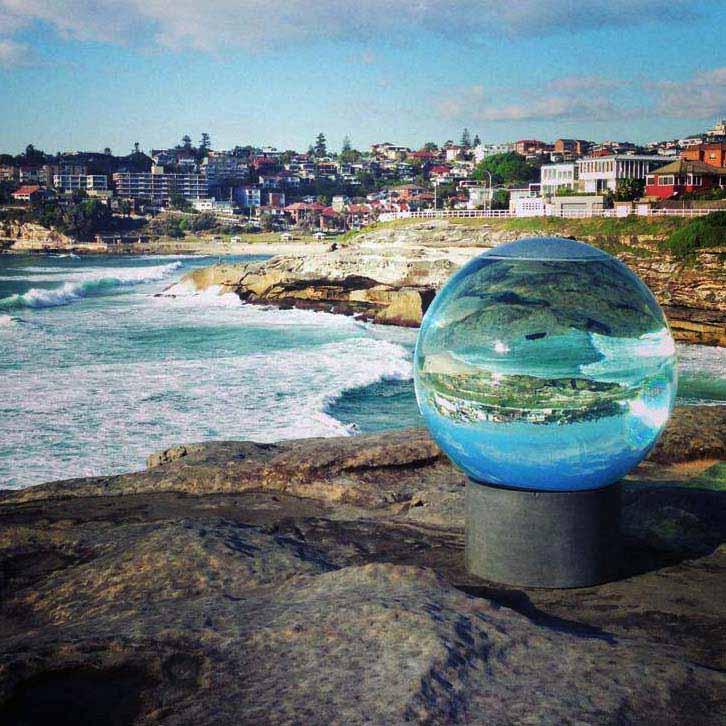

“When director David Handley called me, I didn’t quite understand,” says Sydney architect and sculptural artist Lucy Humphrey of the $30,000 Helen Lempriere Scholarship she was granted in June.

“I couldn’t process it. The generosity is huge.”

Humphrey is one of three Sculpture by the Sea exhibiting artists to benefit of the Helen Lempriere Bequest, a charitable trust managed by Perpetual and established through the will of the late Keith Wood in memory of his wife, Helen Lempriere. Other recipients to receive the $30,000 grants are Paul Selwood and Francesca Mataraga.

Humphrey’s Sculpture by the Sea project, Horizon, was also made possible through the support of generous donors. The sculpture, a 1.5-metre-high acrylic sphere filled with two tonnes of water, has received the in-kind support of Australia’s TLB Engineers, Colorado-based Reynolds Polymer Technology, and Sydney Water, among others.

The giant orb, described by Humphrey as “a mysterious object – a big, bold optical illusion” – was filled on-site with the garden hose of a Bondi resident whose water meter was “switched off” by Sydney Water.

“There’s a real community that has come together around this project,” Humphrey says of her waterside, water-filled sphere. Without the support of donors and grants such as the Lempriere scholarship, sculptors can be crippled by prohibitive costs of materials and transport. Humphrey estimates that a similar sphere might cost upwards of $100,000 to produce commercially in Australia.

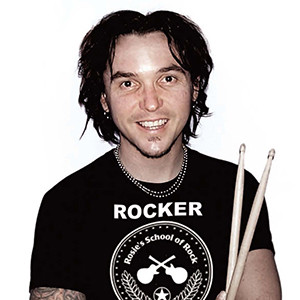

CRAIG ROSEVAR: “What’s more inclusive than drumming? Bam! Nothing.”

Some people’s greatest gift is their ability to see the ‘awesome’ in everyone. Craig “Rosie” Rosevear, Australian 90s rock icon, ex-drummer of The Screaming Jets, and founder of Rosie’s School of Rock, is one of them. When I meet the long-haired, forty-something rocker he is in the middle of a Saturday afternoon’s music program. In the state-of-the-art rock warren that is his Newcastle school, a legion of primary-age and teen guitar groms are holding band meetings. An all-girl drum group is finishing its prep for an upcoming gig, and techy teens carry audio cable from editing suites to studios.

Some people’s greatest gift is their ability to see the ‘awesome’ in everyone. Craig “Rosie” Rosevear, Australian 90s rock icon, ex-drummer of The Screaming Jets, and founder of Rosie’s School of Rock, is one of them. When I meet the long-haired, forty-something rocker he is in the middle of a Saturday afternoon’s music program. In the state-of-the-art rock warren that is his Newcastle school, a legion of primary-age and teen guitar groms are holding band meetings. An all-girl drum group is finishing its prep for an upcoming gig, and techy teens carry audio cable from editing suites to studios.

Before Rosie tells me anything about himself, or the two programs he runs to make rock available to kids with disabilities, he introduces two of his crew. “This is Brit, who is teaching drums,” he beams. “She’s 15 and she’s absolutely fantastic. And Jordan – he’s a mentor for our kids on the spectrum. He’s got the best temperament for teaching and I couldn’t do any of this without him.” Rosie proudly points to photos of the rest of his staff that line the school corridor in a wall of rock-school fame: “We’ve got the best crew ever.”

It’s little surprise that AU:SUM, Rosie’s School of Rock’s program for kids on the autism spectrum, kicked off because of a push by local mums. “Over time parents were coming up to me saying, ‘You’ve done wonders for my kid’,” Rosie explains. “I thought, well that’s good. But then they’d say, ‘Nah, you don’t understand. You’ve done wonders for him: He’s got autism and we never thought he could stand up in front of anybody – you’ve changed his life’.”

Four or five kids come together, choose a band name, write a song, shoot some video, come up with a logo, pick an instrument, then start jamming. At the end of 20 weeks they perform a gig and release their single. Past hits have included classics such as ‘We Are The Best’ by the Killex, and ‘The Fart Song’ by Crusty Volcano.

A KROETSCHIAN AFFAIR: “I have no off switch for my brain”

Not so long ago, on a wet May day, I had a date with Robert Kroetsch.

Not so long ago, on a wet May day, I had a date with Robert Kroetsch.

I was a little nervous as I drove from Banff to Robert Kroetsch’s hometown of Leduc, Alberta to interview the “Father of Canadian Literary Postmodernism”. I didn’t know much about postmodern prose, magical realism, or the development of the ‘Canadian long poem’, but in the end, it didn’t matter. Like so many who met him, I had a Kroetschian experience – surprising, inspiring, life-affirming.

I had expected to meet the 83-year-old in his retirement village home, but instead Kroetsch handed me his cane at the door, climbed into my car and instructed me to drive away. “I’m taking you to lunch!” he said. We drove for half an hour through yellow fields glazed with rain, in search of his favourite dessert. “I come here just for this you know,” he told the waitress when we ordered.

After the loss of his mother, Kroetsch’s motherland of Alberta became his muse. “I spent many years travelling the world,” he liked to say, “but I never left Alberta.” By the time he was 83 and pouring my tea, Robert Kroetsch had received more literary awards than he could poke his cane at. He had written 14 books of poetry, seven non-fiction books, and nine works of fiction, not including the novella he sent to his agent the day before we met.

“I had the idea for it in 1965!” he proclaimed, wielding his spoon.